Written by Anna Li

Sitting in my wheelchair in front of Donald Rodney’s In the House of My Father (1997) at Nottingham Contemporary, I cannot pull my eyes away from the art piece. It is a photograph that captures Rodney’s hand cradling a tiny, fragile house, made of his own skin, peeled off during treatment for sickle cell anemia. The photograph’s size is enormous, making a black hand appear like a vast ground landscape, stretching across the frame, both intimate and monumental. The house, like the hand, becomes more than just an object—it’s a home, a place of safety that is now vulnerable, fragile, and disturbingly exposed.

For Rodney, this house is personal yet universal. It represents a man’s relationship to his body, his illness, and the sense of belonging to a place. An artist was born to Jamaican immigrant parents in 1961 and grew up in Birmingham. The home is a central topic in his works, where the precariousness of cultural belonging and displacement mirrored the fragile nature of identity and health. His illness, which led to his early death, seems to transform the idea of a home from something stable and stone-built to something transient and mobile—an ever-changing reflection of one’s health and identity.

As a refugee from Ukraine in the UK, this strikes me hard. Like Rodney, I was disconnected from my home. It no longer feels like a place of safety but rather a concept that has become soft, vulnerable, and exposed. For me, “home” is no longer a place but something I carry with me. Perhaps, in this constant reimagining of home, there’s something immortal—it’s always there, but it changes with me like my own regenerating skin.

Rodney’s work speaks to a shared human experience, and more importantly, it speaks to the often unspoken vulnerability of being ill, displaced, or disconnected from one’s body. I am happy to see this exhibition in Nottingham because there are not many exhibitions that focus on the intersection of health and suffering of the body in art. It reminded me of Virginia Woolf’s essay On Being Ill, where she lamented the absence of art dedicated to illness. Over 100 years later, we are still in need of works that confront this topic head-on, bringing visibility to those who suffer and reclaiming the body as a site of experience, not just shame or limitation.

Donald Rodney’s soul was unconventional, a quiet storm of brilliance and defiance that radiated through his involvement with The BLK Art Group. Together, they shattered expectations, confronting systemic racism and creating bold spaces for Black British voices in art. As I sit here in my NTU School of Art and Design hoodie, where Rodney once studied, I feel a deep connection to this lineage—a tether to the radical, the profound, and the unapologetically bold.

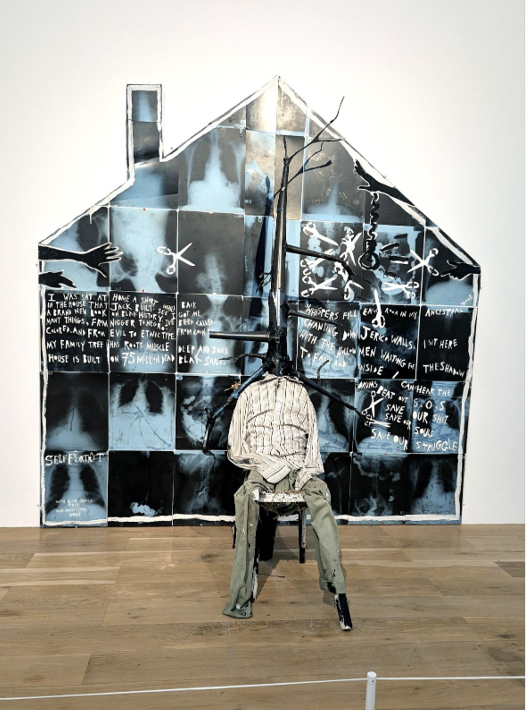

Rodney’s 1987 work, The House that Jack Built, further extends this dialogue. Here, he pieces together a collage of his chest X-rays into the shape of a house—a literal externalisation of his internal body. It is a background for a figure in this installation, a man sitting in a chair, with a branch sticking out of his body like an extension. My first thought was, “Oh, my, it’s his spine!” This hit me personally. I had spinal surgery to correct scoliosis caused by SMA and the memory of the pain I felt after the surgery still lingers. Rodney’s work not only visualises this pain but gives it a shape—his body is on display, and through that, he forces the viewer to confront the internal suffering we so often hide. He does not shy away from the grotesque or the uncomfortable. Instead, he turns it into art that speaks to everyone, not just himself.

Eddie Chambers, Rodney’s fellow artist and curator, once wrote that Rodney used illness as a metaphor for societal and political issues. In The House that Jack Built, the fragility of his body becomes a reflection of the fragility of society. This is not just about one man’s suffering but about the ways in which illness, disability, and injustice mirror larger societal “diseases.”

As I entered the final room of the exhibition, I was taken aback by the presence of a moving, autonomous wheelchair. This was Rodney’s Psalms (1997), an artwork that moves on its own, using sensors and neural networks to navigate the space. It felt surreal—an empty chair moving through the gallery, avoiding obstacles, yet seemingly seeking a purpose. It reminded me of the autonomy and agency we often lose when we become ill or disabled, or because of migration and how technology can blur the lines between the body and the machine. The piece challenges the audience to reconsider the relationship between movement, control, and identity. As someone who navigates the world in a wheelchair, this work resonated deeply with me bringing a new layer to the conversation about autonomy and control over one’s own body.

Donald Rodney’s legacy is immense. He brought the reality of illness into the public eye and used his body as both canvas and message. His works, although deeply personal, transcends the individual and speaks to collective issues of illness, race, and marginalisation. I am honoured to have seen his work in person, and I know that his art will have a lasting impact on me—not only as an artist but as someone living through my own experiences with disability. Rodney’s art is not just British art history; it is a testament to the power of making the internal external, of making the personal political, and of finding beauty and meaning in even the most fragile of homes.